The key ingredients to a better blockchain, Part VIII: Usability

Our understanding of what makes a blockchain successful is becoming clear. What will it take to succeed?

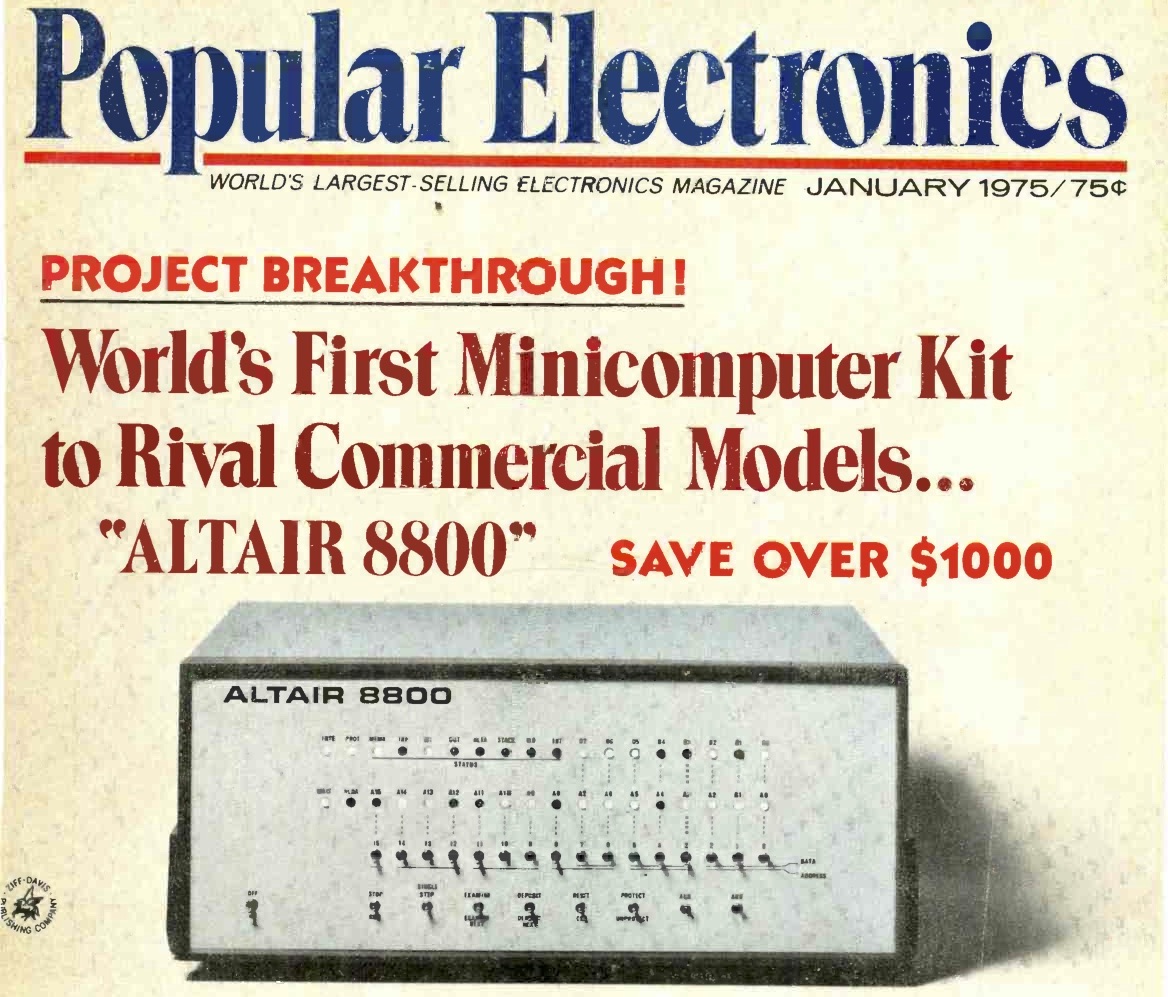

The Altair 8800 didn't have great usability by modern standards. Released in 1975, it arrived as a kit that had to be assembled, and could only be programmed and interacted with via a series of switches and lights on the front panel. Nevertheless, as the first commercially successfully personal computer, it's generally regarded as having kickstarted the microcomputer revolution. Blockchain is roughly as usable today as the personal computer was in 1975, but it's improving by leaps and bounds.

[This is part of a multi-part series on the key ingredients to a better blockchain. I recommend starting with part one, Tech and Protocol. See the full list of articles in the series.]

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Layer zero: the social layer

- Layer one: the base layer

- Layer two: the application layer

- Conclusion

- Notes

Introduction

In 1975, at the advent of the personal computing revolution, to be a computer user effectively meant that you had to be a software developer. That was okay in the beginning, as all technologies begin this way. Needless to say we’ve come a long way since then. Billions of people now carry supercomputers in their pockets that require no special expertise to use, and many of our daily activities involve using computers without our even realizing.

If you ask me, in terms of the technology lifecycle, blockchain today is about where personal computing was in the mid to late seventies. It’s proven that it is useful and it holds great potential, but it’s still notoriously hard to use. Until recently, this was due mostly to limitations in the base layer: even the best UX can’t make up for severely limited transaction throughput! To put this in terms of personal computing, no application, no matter how fancy, could make up for the need to swap multiple floppy disks in and out in order to overcome the limitations on storage and memory of early personal computers.

However, the blockchain base layer has come a long way the past few years, and many of these initial, technical challenges have been overcome. Usability lags somewhere behind. While the blockchain space has no shortage of brilliant technical minds, in relative terms there has been a lack of focus on product and design. This has begun to change, and modern blockchain platforms and the tooling built on top of them have begun to incorporate many of the same design best practices that have permeated the Web2 world.

A few years ago it was okay if a blockchain platform was not user friendly and had terrible tooling, and if building an application was next to impossible, because the few users of these platforms were technically sophisticated hobbyists with time on their hands. Until quite recently, it was common for even the largest blockchain teams not to have any designers. This is no longer the case. Modern blockchain platforms now need to prioritize usability if they want to stand a chance against competing Web2 and Web3 platforms.

How can a blockchain platform prioritize usability? Here are some ideas to consider now to stay ahead of the game. As these ideas touch every layer of the stack, from the social layer (“Layer zero”) to the blockchain base layer (“Layer one”) up through the application layer (“Layer two”), we’ll examine each in turn.

Note that, while design in this context usually refers to user experience (UX), i.e., things that make it easier for a user to use a platform and the applications built on it, importantly, it also includes developer experience, in the sense that it should be as easy as possible for developers to get started building applications on a platform as well.

Layer zero: the social layer

Blockchain technology may be very exciting but, at the end of the day, it needs to serve human needs and use cases. It also relies upon people to come together, form communities, and invest the time and energy to develop not only the base layer but multiple layers of tooling, infrastructure, and applications on top of the base layer. The platform must therefore be approachable and accessible to as many people as possible. The social layer is the true bottom layer of blockchain, because without a healthy community of contributors and users, it doesn’t matter what gets built on top. Usability begins with communicating clearly and concisely using design principles, design proposals, and documentation.

Recognize that brand and principles matter

The best products, experiences, and brands don’t spring into existence by accident. They’re the product of a great deal of careful thinking, planning, and strategizing on the part of marketers, designers, engineers, executives, and other strategists. For top companies and their products, everything is connected and nothing is accidental. What you feel when you see an advertisement serves what you see on a landing page, which serves the experience you get when you download the app, which in turn serves the followup email you receive a few days later, which in turn serves your ongoing experience using an app or service. It’s all part of an intentional, holistic experience. It’s often referred to as the customer journey, the marketing funnel, or simply the “brand.”

Up to now these ideas have been relatively foreign to the blockchain space, but that comes at our detriment. There’s a reason that big, profitable companies spend heaps of money on branding and marketing: like them or not, they work. A user’s decision to try something unfamiliar, to download an app or subscribe to a service, is as much about the initial marketing touchpoints that led them to the product in the first place as it is about the product itself. This is doubly true for a technology as disruptive as blockchain that requires fundamental changes in consumer behavior!

If we want our platforms and the things built on them to feel approachable and familiar to everyday users, we need to give serious thought to how they are branded and marketed. This includes visual branding: logos, colors, typefaces, the visual design of apps, websites, emails, advertisements, and swag (such as the ubiquitous crypto T-shirt). But it also includes less obvious things such as copy, messaging, onboarding, and user experience. Jeff Bezos put it best when he said, “Your brand is what people say about you when you’re not in the room.” A brand is the whole bundle of thoughts and feelings that people associate with your organization, platform, product, service, and community.

Branding and marketing are easiest when your product or service speaks for itself: in other words, when you create clear value and have a clear, honest message to deliver. In this respect, blockchain and Web3 have an advantage over incumbents because our message—one of privacy, responsibility, and self-sovereignty—is apropos, modern, and refreshingly honest.

A good starting point is to create a set of design principles. In addition to the sort of visual design guidelines described above—logos, colors, typefaces, etc.—this should include high-level user experience design goals that outline how you’ll make decisions and approach tradeoffs in the design process. For inspiration, see Blockstack’s Can’t Be Evil engineering principles, The New Tech Manifesto, Simple, Durable, Yours, and the Web3 Bill of Rights. The principles laid out by each of these have big implications for usability. For instance, if you prioritize convenience and trust, you may want to manage a new user’s private keys for them, at least for a time. If you instead prioritize safety and self-sovereignty, you’ll need a different approach, one that likely involves educating the user to take more responsibility. By the same token, prioritizing simplicity means rethinking a lot of what we’ve come to expect from a modern computing experience: clutter, notifications, customizability, etc.

Invest in good documentation

All software requires documentation. While in theory simple, elegant, well-designed software should be intuitive and easy to use, and therefore may not require as much documentation, in practice documentation is essential even for well-designed software and should really be thought of as a product itself. Some classes of users tend to rely on documentation and will be discouraged if it doesn’t exist or is poorly written. Some use cases, such as an API or SDK, require developer-friendly documentation to be useful. Its complex, novel nature means that documentation is even more important for a blockchain platform than it is for other types of software.

Every aspect of joining and contributing to the platform should be well documented: downloading, compiling, and running a full node, participating in mining/validating, contributing to infrastructure, tooling, and core development, building applications, and using tooling and applications. The people best positioned to write documentation are often the developers who build the platform and tooling, but many developers don’t enjoy writing and maintaining documentation. Establishing good practices to write and maintain good documentation is beyond the scope of this article, but there are ample resources available on this topic. A good starting point is to require that documentation be written or updated to correspond to every code change, and not allowing any code to be committed without the corresponding documentation.

Good documentation can be difficult and expensive to create and maintain, but it’s worth the cost. In addition to relying on developers as the primary authors and maintainers, consider hiring someone whose full time job it is to write and maintain documentation. You may also consider letting community members write and maintain documentation in exchange for grants or bounties.

To see what’s possible with good documentation, see the Stripe API docs, which are generally regarded as being among the best in the tech industry.

Hire a designer

Developers can and often do get software from zero to one, i.e., from concept to a workable prototype. However, if you want your software to be usable and approachable, especially to non-technical users, you’ll need to enlist the help of a professional designer.

In spite of this truism, it’s remarkable how many large, well-funded blockchain platforms have few or no designers on the core team. Getting designers involved early in the core design and development process can help avoid pitfalls and result in a much more user-friendly platform. Usability has a surprising number of implications on the design of even the base layer (layer one). As just one example, the fact that Ethereum requires that gas be paid using ETH, and that the transaction processing capacity of the network cannot be scaled up or down, has serious implications on the UX of any application built on the platform. All users of layer two applications must already hold ETH even if those applications use a different token, and the amount they need is unpredictable and varies depending on network load. This is counterintuitive to many users since the status of the overall Ethereum network may have no obvious, direct connection to the application the user is interacting with.

Note that there are many different kinds of design, and you should carefully hire a designer or agency on the basis of your needs and their skills. The two most critical types of design for most digital products are visual design and user experience (UX) design. It’s rare to find a designer that is well-versed and skilled in both, so it’s safest to hire for these separately.

Take a product approach

There are many different ways to design and build software. The most straightforward way is to just build whatever solves your own problem. This is what most blockchain teams do, and until recently, it sort of made sense because blockchain had very few users and very few use cases.

Successful Web2 companies approach the software they build as a product. Rather than building what the internal team thinks is best, they spend a lot of time and energy on customer discovery, affectionately known in Silicon Valley culture as “get out of the building.” This process can take many forms, but at its simplest, it means explicitly stating the assumptions that you’re making and building into the platform, systematically testing those assumptions by putting your design and product in front of users as much as possible, and, when in doubt, deferring to the user’s needs over your own preferences and inclinations. In other words: listen to your user and observe their actions. This process often involves design thinking, customer discovery interviews, usability testing, and focus groups. It’s especially important that the process include non-developers (unless of course your product is designed specifically for developers).

The product approach also has implications on the way you think about and communicate about your software. As a concrete example, most blockchain teams tend to communicate primarily or exclusively using GitHub. There’s a “README” and/or a “CONTRIBUTING” file in the main repository that (hopefully) explains how to download, use, and contribute to the software. The software probably only runs on the command line, and may be tricky to configure and run. Development platforms such as Linux and macOS are typically supported, while Windows is often only partially supported, or not supported at all.

By contrast, a product mindset dictates that you put yourself in the shoes of the user, consider the onboarding experience, and make things as easy as possible. Rather than writing documentation on GitHub in markdown format, which is friendly to developers, you’ll want a landing page with documentation that’s accessible to all users. You’ll want a UI that’s as easy as possible to set up and install. You’ll very likely want Windows support, since many potential users run Windows. You may want to brand and market your software less as a command line utility and more as an app that anyone can download and use. You may want a blog and/or a Twitter channel to make release announcements, etc.. These straightforward steps will go a long way towards making your software, platform, and organization approachable and accessible to as many people as possible.

Layer one: the base layer

With these basic social building blocks in place, we can turn to the base layer infrastructure. In the case of blockchain, this typically includes the full node software itself, all of its subcomponents (database, P2P networking, virtual machine, consensus, etc.), the protocol, and certain low-level tooling. While many blockchain developers tend to regard the base layer as abstracted away “under the hood,” inscrutable, and thus exclusively within the purview of engineers (as opposed to designers), in fact there are myriad design decisions that need to be made at this layer that have big implications for the usability of the entire platform and applications running on it. Given how difficult it can be to change the base layer, to ignore this fact is to condemn a platform to usability headaches down the road.

Ensure the software is easy to run

As described above, good documentation can go a long way towards making your software accessible and approachable, but the software itself should also be packaged and released in such a way that even non-developers can easily download and run it. It should not have outrageous resource requirements: it should run well on consumer-grade hardware without making the system unusable. If you only want a small number of professionals to run nodes, then this probably doesn’t matter, but if decentralization matters to you, then your software must be extremely easy to download, install, run, maintain, and upgrade.

Sadly, this is still not true for most blockchain platforms. I ran an Ethereum full node on my consumer-grade laptop for a long time, but I gave up last year when it began to consume too much disk space.1 I try running nodes for many platforms, both in order to learn and to support these projects, but nine times out of ten, I give up after a few hours when I run into undocumented errors, or when the burden of keeping the node running becomes too great.2

Ideally, running a full node should be as easy as downloading an app and running it on your own device. It should only take a few minutes to set up. It should not require a cloud VM, professional skills, or a huge investment of time and money.3

Why does this matter so much? In addition to the fact that more nodes means more decentralization and more network security, there’s also a social reason that is even more important.

The hidden strength of platforms like Bitcoin and Ethereum, and a big reason each has been so successful, is accessibility: how easy it is (or, at least, used to be) to run a full node and to become a fully-fledged peer, a first class citizen of the network. In fact, the first blockchain platform to achieve mainstream adoption will likely be the first one that makes it possible to run a node anywhere: on your laptop, mobile phone, VR headset, toaster oven, and automobile. People everywhere are fed up with the unfairness and inequity of the social, political, and economic world order, and one of the most attractive things about blockchain, and one of the ways in which it is the most meaningfully different from the existing order, is the opportunity it gives people to transact as peers without requiring trusted intermediaries such as banks and lawyers. In order to be accessible, a blockchain needs software that’s easy to install, run, and use.

Make onboarding easy

Software that’s well documented, marketed, and easy to install and run are great first steps towards base layer usability. However, there may still be other obstacles to joining the network and community.

One such obstacle many users encounter trying to join a network is the chicken-and-egg problem of needing tokens before they can transact. How does a user get their first tokens? Directing users to buy them on an exchange is not a great answer. This generally requires identification (for KYC/AML purposes) and a bank account or a credit card, and it can take a few days for the account to be approved.4 What’s more, some users in some jurisdictions may not be able to complete this process at all for various reasons.

Application developers may be tempted to hand users their first few tokens, or make them available through a faucet as a workaround, but this is not without some challenges as well. For one thing, on many networks, including Ethereum, fees can only be paid in the base currency (ether, in the case of Ethereum), so handing a user an application token alone does not help. For another, without a Sybil resistance mechanism, a single adversary can drain a faucet and prevent others from using it.

There are a number of creative approaches to work around this friction. Some Ethereum applications now support gasless transactions, where someone else pays the fee for a new user’s first few transactions. Why would someone else want to pay the cost of onboarding a new user? Application developers may be able to factor this in to the cost of acquiring a user. However, this solution has become more expensive as Ethereum network congestion has increased.

Another approach is to allow a user to begin interacting with your application, and to create value for them, before requiring them to obtain tokens. Some of the most well-designed applications actually allow users to earn their first tokens (rather than having to buy them). While Decentraland requires that you have an Ethereum account to login, it does not actually require that you make any transactions or have any tokens unless and until you decide to visit its marketplace. Cent does not require tokens to sign up, and lets you earn tokens by posting content. Brave Rewards works similarly.

The base layer can make onboarding easier by allowing fees to be paid in multiple tokens (although this is not without complexity). It can also facilitate layer two solutions like gasless transactions (see next section). Even better, it should be possible for a user to permissionlessly mine their first token using existing hardware.

Facilitate layer two

Running things on the main chain will always come at a premium, both in terms of time and cost, which inevitably has a cost in terms of usability. So one great way to improve usability is to keep as many things off the main chain as possible.

One common approach is sharding: i.e., dividing the blockchain into many smaller logical chains, known as “shards.” Each shard chain can host a cluster of related applications, or, in the extreme case, a single popular application. Polkadot, for instance, is designed to host many application-specific shard chains known as parachains. Some protocols allow individual chains to set their own policies with respect to fees, security, and finality.

Another approach involves layer two solutions that are not themselves fully-fledged, highly secure base layer blockchains, such as sidechains and state channels. The base layer can facilitate these solutions by including certain VM opcodes. As one concrete example, Ethereum’s CREATE2 opcode, introduced last year, significantly reduced the cost of opening state channels.

To a large extent, the ability to do interesting things off-chain and at layer two relies upon the existence of robust layer two tooling (on which more in the next section).

Mobile support

Little to no blockchain software today is mobile friendly. The implicit assumption seems to be that most users of blockchain prefer to use a desktop or laptop, and that most Web3 applications work just fine on desktops and laptops. In this respect, blockchain applications contradict the global trend towards mobile, mobile-first, and mobile-only.

This is partly explained by real technical limitations. Blockchain is resource intensive and it’s nearly impossible to run a full node for any major blockchain on a mobile device with constrained resources.5 However, there are things that can be done at the base layer to make things easier for mobile.

One is to make full node software as lightweight as possible. In most existing blockchain platforms, node software is all-or-nothing: you either run a full node or you run nothing (and outsource trust entirely to those that do run nodes). In fact, participating in a blockchain, and in the consensus formation process, is not black and white. There could and should be many shades of gray. The concept of a light client is as old as Bitcoin, but the options for running a light client on mobile are severely limited even for the most popular blockchains. It would be interesting to see full node software that would run full-throttle on the most powerful systems, but would degrade gracefully to enable it to run on more resource-constrained devices such as mobile phones. Similarly, node software should consume more resources when they are available—such as using more bandwidth when a phone is connected to wifi, and more energy while it’s charging—and switch into a “power nap” mode when they’re not.

Of course, mobile support doesn’t stop at the base layer. It is arguably even more important that it be as easy as possible to run layer two applications on mobile (on which more in the next section).

Make transactions faster

In every blockchain, there is a fundamental tradeoff between, on the one hand, time to finality (how long it takes a newly-mined transaction to become a canonical, irreversible part of the chain) and security and decentralization on the other. Other things being equal, a lower block time is of course better from a UX perspective, since it means that application responsiveness will be faster and users won’t sit around waiting as long for transactions to be confirmed. However, if the time between each block becomes too short, more miners will start to produce so-called “uncle” blocks that never make it onto the chain, which reduces security. A smaller number of block producers can produce and exchange blocks more quickly, but having a small number of block producers is less decentralized, less secure, and less censorship resistant. Eos, for instance, has a subsecond block time, but only 21 sanctioned block producers at any given time, leading to criticisms of a lack of decentralization and censorship resistance.

Each blockchain community will have to do its own research, parameterization, and simulation to choose a block time that isn’t so fast as to sacrifice too much security, but isn’t so slow as to make applications unusable and frustrate users.

Of course, while block time is a crucial factor, user experience at the application layer depends on a lot more than block time. There are other tricks that can be used to improve user experience. Keeping most transactions off the main chain is one of them. (More on this, too, in the next section).

Make key management easy

As discussed previously in this series, good account hygiene means encouraging users to escape the “one keypair per account” mindset, and making it easy for them to do so. Encouraging users to use a different account for each application is a step in the right direction and improves privacy, but it means the user needs to maintain funds across many accounts, which can be tricky.

Another approach, pioneered in Ethereum and supported by new platforms such as NEAR Protocol, is to eschew keypair-based accounts in favor of smart contract-based accounts, allowing many keypairs to be associated with a single account. This has numerous benefits: a user can have a backup account key that’s stored securely, and keys can be created per-application with various degrees of permission (similar to the familiar Web2 OAuth flow). It also enables progressive security: an account can start out inside a hosted wallet and, later on, the user can take more control, or full control, over the account by updating the keypairs that have access to it.

This can be achieved at layer two—witness the pioneering use of Universal Logins in Ethereum—but it may be cheaper and easier if support is enabled at the base layer, as in NEAR protocol.

Layer two: the application layer

Most of the investment in improving blockchain technology over the past few years has flowed into layer one. This is understandable, since blockchain still faces major hurdles at the base layer including scalability, decentralization, and governance. However, as mentioned above, enough progress has been made in overcoming these hurdles at the base layer that the burden of improving usability has begun to shift towards the application layer. The rapid, enormous increase in usability of Web2 applications over the past decade should give us hope that, as blockchain base layer infrastructure continues to mature, we can adopt many of the best practices of Web2, combined with fresh thinking to address challenges unique to Web3, to ensure that Web3 applications are as easy and pleasant to use as their predecessors.

Balance usability and decentralization

It can often feel as if it’s impossible to achieve both usability and decentralization. This is one of the biggest dilemmas facing teams that want to build real world applications on blockchains today. On the one hand, what’s the point of building a decentralized, blockchain-based application, if that application won’t be usable by, or accessible to, anyone but the most tech savvy blockchain insiders? On the other hand, what’s the point of building an application on blockchain in the first place if that application is run in a highly centralized fashion and doesn’t make use of unique features of blockchain like censorship resistance?

This dilemma manifests in various ways. The most straightforward example is that loading and interacting with applications running on decentralized platforms can be frustratingly slow. The centralized applications that we’re used to interacting with have been highly tuned and an enormous amount of money, design, and engineering has gone into making them as fast, responsive, and reliable as possible. Few users will have the patience to interact with applications that are slow to load or have slow response times.

Governance is another good example. While decentralized governance is exciting and has great potential, it also introduces a host of challenges. In a centralized Web2 application, fixing bugs or upgrading the software is relatively straightforward, and it’s not uncommon for popular, centralized applications to release updates as often as daily. By contrast, for an application such as a smart contract that’s governed in a decentralized fashion, even a routine upgrade or bugfix becomes a complicated coordination problem. How do you communicate to users about the upgrade? How do they know to trust you? How does everyone switch to a new application at the same time?

A third example is key management. Web3 encourages responsibility, self-sufficiency, and self sovereignty over data and assets including identity and cryptographic tokens. However, most users today expect to be able to ask a trusted third party—their bank, the phone company, or Facebook—to reset their password, or fix problems for them. How do we train users to understand that if they manage their own keys, there is no one who can fix things for them when they break?

In reality, decentralization is not black and white. It’s a sliding scale. Different projects will choose different points on the spectrum, and, even more importantly, the best-designed projects will allow users to gradually accept more sovereignty along with the responsibility that comes with it. One promising, novel approach is progressive decentralization: in the beginning your product or platform can look and feel more like a traditional, centralized application, but over time, as it develops product market fit and as the community grows, more and more control can be ceded to the community. Projects such as Compound are proving that this model works.

Invest in good tooling

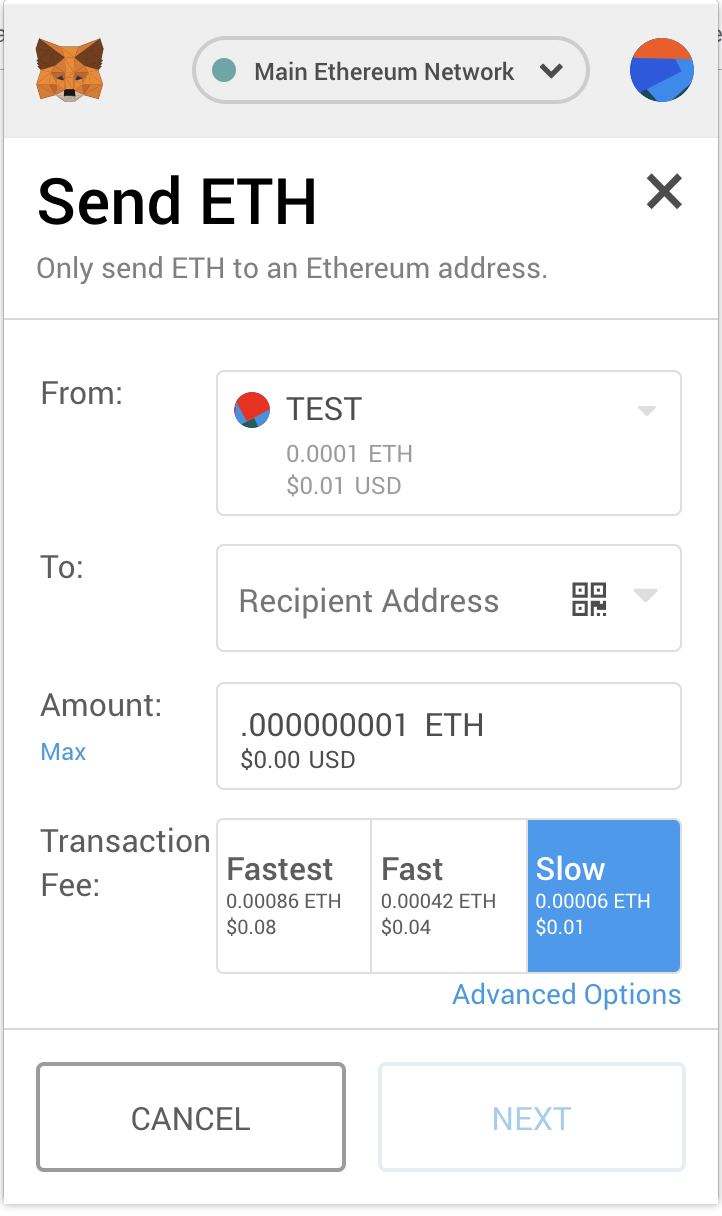

Good tooling can make a world of difference in usability. It can hide the complexity of the base layer, make a platform more accessible and approachable to a broader set of users and developers, and foster a rich community and ecosystem of applications and use cases. In the case of blockchain, the simplest example is the “login screen” a user first sees: generally a wallet application such as Metamask. User friendly wallet software can make onboarding much easier and prevent users from abandoning a project out of frustration before fully onboarding.

Tooling also has an enormous impact upon the lives of developers. Compilers, debuggers, version control, and orchestration tools can save programmers many hours and make them more effective. The best tools make developing software for a given platform a joyful experience. This is especially true in the Web3 space, where applications are typically harder to debug and build, harder to deploy, and harder to monitor and maintain than other types of applications. Contrast, for instance, the experience of developing an application using Apple’s integrated Xcode development environment, where a developer can run, debug, and profile an application in a sandbox with one click, to the experience of developing a smart contract application where no such mature, integrated tooling exists. Blockchain developer tooling has improved by leaps and bounds over the past few years, but it still has a way to go before it can approach the experience that most professional developers are used to. There are some technical aspects of blockchain that naturally make development harder, such as virtual machines and the distributed nature of the system, but most of these can be abstracted away with mature tooling.

Developing good tooling isn’t cheap, but it’s a worthwhile investment and can make the difference between a project remaining fringe and successfully appealing to the mainstream, both users and developers.

Hide the details

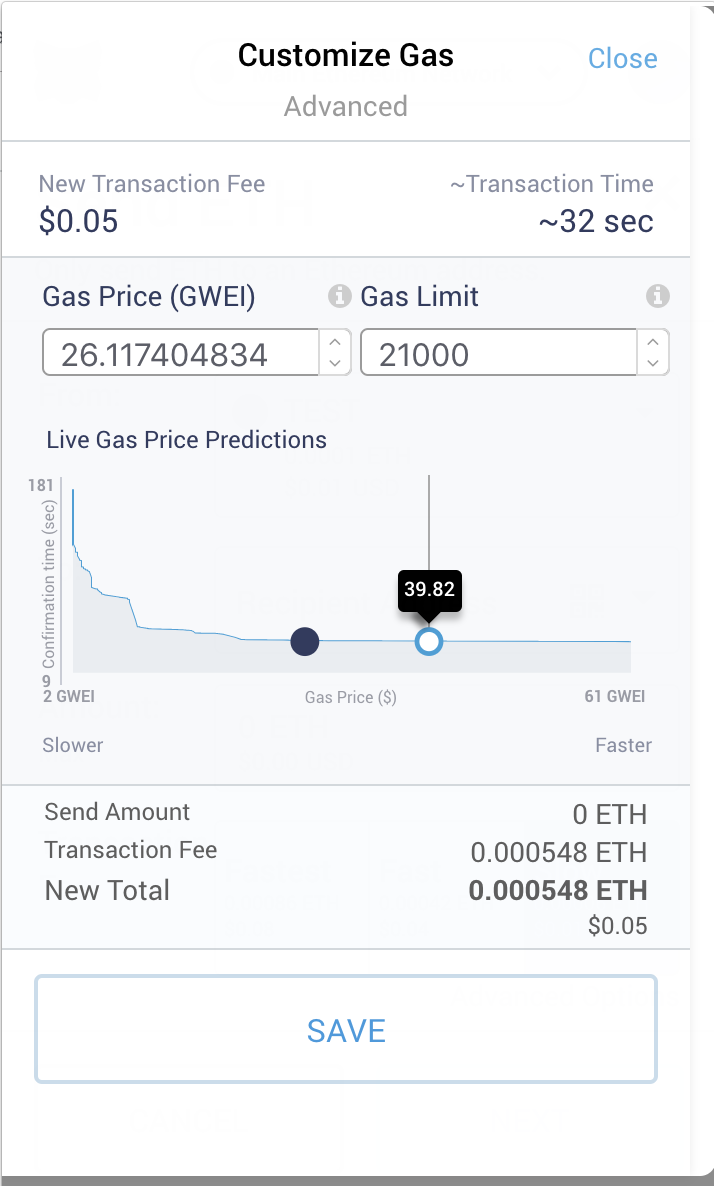

Metamask, one of the most popular Ethereum wallets, does a great job of hiding the details: by default it picks a reasonable gas price for you, but you can also customize the gas price when sending a new transaction. Would that gas were always this cheap! (Image source)

Blockchain is a complex technology, and one reason that it has failed to achieve mainstream appeal is the way in which that complexity surfaces very quickly during onboarding, when making even basic transactions, and when building and interacting with applications.

However, many of the technologies that modern consumers interact with on a daily basis, from mobile phones to automobiles to airplanes to satellites, are as if not more complex than blockchain. The difference is that these more mature technologies do a better job of hiding complexity from the user. The driver of a modern automobile doesn’t need to know anything about torque, engine size, or catalytic conversion. Similarly, someone using GPS technology doesn’t need to know anything about modulation, multilateration, or orbital inclination. Why should a user of blockchain technology need to understand gas, probabilistic finality, or elliptic curve cryptography?

Well-designed applications and tooling can go a long way towards hiding complexity. Wallet software should make reasonable, default choices about things like fees and time to finality. Applications should be designed so that they automatically select a reasonable set of defaults and “just work” out of the box for most users and most use cases, with an “advanced mode” that allows sophisticated users to fine tune things like fees. This is like using GPS software that makes navigation easy, but allows the user to manually select a set of satellites to track, a feature that most users will never use nor even need be aware of.

Promote UX best practices

Blockchain projects and communities seem to have a penchant for blank slatism, i.e., for rejecting outright many of the principles, ideas, and practices of the Web2 world. This is understandable since the Web is broken in some important ways. However, there is a lot that we can learn from the Web, broken as it is. It’s important that we not throw the usability baby out with the Web2 bathwater, so to speak! Many smart designers and developers have been iterating on design and UX best practices for a very long time, and it doesn’t make sense to ignore these established principles entirely.

There are several reasons for this. The most obvious is the need to reduce friction, make it as easy as possible for new users to onboard, and shrink the time to value between when a user signs up and when they first experience a “this is amazing!” moment. A second but no less important reason is to give users an experience that feels familiar. Many mainstream users have invested a lot of time and energy in getting familiar with the well-designed, mature tools that they use today and they are not keen to relearn all the basics. This is doubly true for tools that are slower, clumsier, and less user-friendly than the ones they’re used to. A third reason is that good design provably works—not only to make life easier for your users, but to increase conversion rates and user stickiness.

The list of usability best practices from Web2 is too long to cover here, but some low hanging fruit that can make a big difference for Web3 applications today include auto-generating accounts and storing them in browser storage (rather than requiring a wallet application such as Metamask—see note above about hosted wallets and progressive security), displaying readable names wherever possible rather than the long hexadecimal numbers that are commonly used to display account addresses, and promoting mobile first. As much as possible, make it possible for users and developers to continue using the tools, applications, and frameworks they’re already familiar with. For a treasure trove of other good ideas, see the excellent Web3 Design Principles.

Conclusion

Many blockchain projects and applications have chosen to track vanity metrics such as funds raised or tokens traded rather than more meaningful metrics such as useful applications built or lives touched. Rather than prioritizing the number of unique, active users, standard practice for mainstream Web applications—a metric which remains tiny for even the most popular blockchain applications—the overwhelming mindset in blockchain communities has been, “If you build it, they will come.” If the past few years have shown us anything, it’s that this attitude is unhelpful, unrealistic, and hubristic: a lot of seemingly exciting things have been built, but the users still have not come. No one signs up for a platform for the underlying technology. They sign up for applications that solve problems and do useful jobs. The infrastructure must serve the application, not the other way around.

It’s easy to dismiss these failures when you really feel like you’re changing the world. It’s easy to rationalize and convince yourself that mainstream users may not get blockchain yet, but eventually they will. After all, blockchain is a zero-to-one technology: it makes possible things that simply were not possible before.

All of that may be true. And maybe it’s okay that most existing blockchain platforms and applications are difficult to use for all but the most sophisticated, tech savvy users. Most technologies start this way, after all. But blockchain and the things built on it only stand a chance of having mass appeal if and when design improves, and blockchain applications begin to resemble applications that users are already familiar with.

The base infrastructure of blockchain is finally mature enough to build truly user friendly applications. Now is a great time to invest in better design. Your users will thank you!

Notes

This article is part of a multi-part series on the key ingredients to a better blockchain. Check out the other articles in the series:

- Part I: Tech and protocol

- Part II: Decentralization

- Part III: Community

- Part IV: Constitution

- Part V: Governance

- Part VI: Privacy

- Part VII: Economics

- Part VIII: Usability

- Part IX: Production Readiness

- Part X: Sustainability

-

I was running on a Macbook Pro with a 1TB internal SSD. I gave up when the required space exceeded around 300gb, because this didn’t leave me with enough space to do other things. Since then the required space to run a full node has grown to over 500gb. It requires a SSD, and can no longer be run on a HDD. It now also takes several weeks to fully sync a new node from scratch, and if your system can’t keep up or you lose your Internet connection, you may never catch up. Here’s a humorous and detailed thread on a recent attempt. ↩

-

And I do this professionally, and have access to powerful infrastructure. If I struggle this much to run a full node, I can only imagine how less experienced, less motivated users might struggle to do so. For a good example of the steps required to run a validator on a production network, check out these docs from Celo. I tried to run a validator, and eventually gave up. ↩

-

Incidentally, this is our goal at Spacemesh. It only takes a few minutes to download an app and join the testnet. ↩

-

This video does a great job of parodying what the onboarding experience feels like. ↩

-

This includes battery, compute, and memory, but for blockchain the biggest limiting factors are storage and bandwidth. ↩