Much Ado About Decentralization

Decentralization is oft-invoked but ill-understood. Before decentralizing all the things, let's talk about what decentralization is good for.

Decentralize all the things? Maybe let’s start with some of the things, some of the time :) Lots of decentralized magic happened in this room, at ETHDenver. Photo by the author.

I’ve written about how we might think about decentralization in the context of blockchain, but I want to zoom out and think about it a little more broadly. Decentralization is a topic that comes up more often than probably any other topic in the blockchain community. Yet I’ve noticed that we tend to take it for granted—that is to say, we accept it at face value, as an end in and of itself, without defining it or debating where and why decentralization is valuable. This fervor is best captured by the oft-repeated mantra, “Decentralize all the things!”

Decentralization has many benefits, and of course it also has many costs. Since the topic comes up so often, I thought it would be fun to attempt to write a canonical list of the arguments in favor of decentralization, as well as the arguments against it. I hope this might be helpful as a reference for anyone considering which things to decentralize, and when, and how :)

I’ll start with the below list of arguments in favor of decentralization, and I’ll follow it later with a list of arguments opposed to it. This is a living document! In other words, I’ll continue to add things to this list as they come to mind. Please feel free to suggest additions by commenting below.

The meaning of decentralization

Where did the decentralization movement come from in the first place? Of course, it’s much older than Bitcoin and it’s about a lot more than blockchain. If I had to boil it down to its barest essentials, I would say that decentralization is about trust and resilience.

Let’s start with trust. In 2009, in the midst of the global financial crisis, global distrust in banks, governments, and in all systems and forms of authority reached the highest point in living memory. One manifestation of that distrust was the global trend towards populism and the emergence of demagogues like Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro. Another was the emergence of Bitcoin. There’s a reason that Bitcoin emerged when and how it did.

When you interface with a centralized system—whether a bank, a government, a company, a piece of software, or anything else—you by definition are placing your faith in the operator of that system. In a bygone era of trusted experts and institutions, that seemed okay to a lot of people, but it’s a much harder sell today. Banks can lock your account or delete your balance, and Google or Facebook can unilaterally and arbitrarily block your account or change their API. By contrast, decentralized systems remove the need for some or all of this trust—hence they are often referred to as “trustless.”1 They radically change the dynamics of the system: as opposed to a client and server model, where there are privileged “nodes” in the “network” that have privileged access to the system, in a fully decentralized network, everyone is a peer and has precisely the same privileges. Everyone can see precisely the same information, and everyone can participate fully, according to one set of rules.2

The most obvious real-world example of such a “trustless,” decentralized system is Bitcoin, which was created by a group of people who do not trust banks with their money, nor the United States government with monetary policy. This group is deeply skeptical of the state in general.

Decentralization also leads to resilience because it is very hard to kill a system without a leader, an operator, or a single point of failure. Real-world examples of well-known systems that are designed in a decentralized fashion for resiliency and redundancy are the Internet, the army, and the brain. Perhaps the best example from recent history is BitTorrent, which arose as a decentralized response to the way authorities cracked down on centralized file sharing services such as Napster. In this respect, a decentralized system is like the hydra: chop off one head, and three others appear somewhere else.

Let’s cut to the chase: in addition to reduced need for trust, and greater resiliency, what are the other benefits of decentralization?

The benefits of decentralization

Decentralization reduces the number of people and things you need to trust

As discussed above, every centralized system has a central operator, and if you interface with such a system, then you are explicitly or implicitly trusting that operator. If you use Facebook, you trust Facebook to deliver your posts and messages to your friends, and to show theirs to you. If you use Google products, you trust Google to show you the most relevant search results, to deliver your email, to keep your files safe, etc. If you use, or save, the USD, you trust the United States federal government to manage the currency well: not to devalue it by issuing too many dollars, not to take on too much debt or default on that debt, etc. By contrast, if you host your own email server (email being, fundamentally, a decentralized protocol), use a decentralized social network like Mastodon, or use bitcoin instead of dollars, there is no centralized operator that you need to trust. Trust is in short supply these days, so I think this logic resonates for many people.

Decentralized systems are more adaptable, resilient, and longer-lived

Whereas a centralized system has many single points of failure—an individual leader, a company, a piece of infrastructure, a single regulatory regime, etc.—decentralized systems have no single point of failure, so are impossible to decapitate and very difficult to kill. They’re more likely to gradually fade into obsolescence or irrelevance than they are to outright die. An illustrative example is language, which is highly decentralized. There have been many attempts throughout history to kill languages, but I’m not aware of any that succeeded. A language may not be officially sanctioned, or may even be forbidden from being spoken in public, but as long as there’s a small pocket of speakers somewhere who prefer using the language with one another, it cannot be said to have died.

Decentralized systems tend towards antifragility

In fact, it goes beyond resilience. When a system is antifragile it not only withstands stressors, but stress actually makes the system stronger. This property is much more likely in a decentralized system than in a centralized system. If you tried to kill Bitcoin by swatting a bunch of nodes, it’s likely that not only would those nodes be quickly replaced, but indeed, even more would appear to replace them. Community, too, can become more resilient in the face of stressors. Attacking a network or community may serve to highlight its importance or legitimacy. This may inspire more people to get involved, and those people will splinter into many small groups and communicate in many different ways over many different channels, making it much harder to quash or even monitor those communications. Another good example of antifragility is a federal system of government: individual states can observe and learn from, and make up for, each others’ mistakes, such that the overall federation becomes stronger in response to stress.

Decentralization enables censorship resistance

This is closely related to trust. In a centralized system, the trusted operator can unilaterally decide to censor any party, at any time, often with impunity. If Facebook decides not to deliver your messages, or if Twitter decides to shadow ban you, or if Google decides to shut down your account for an ill-specified “terms of service violation,” you have very little recourse. If the United States government decides to put you on a sanctions list, you have even less recourse. If you choose to use a centralized system, you thus have very little choice but to trust the system’s operator not to censor you. In a decentralized system, by contrast, no one party nor any minority group of colluding parties has the power to censor another participant. Free speech is as important as ever, and in an age when more and more of our communication is occurring online, mediated by centralized platforms and unaccountable companies, the importance of this point cannot be overstated.3

Decentralization enables permissionlessness

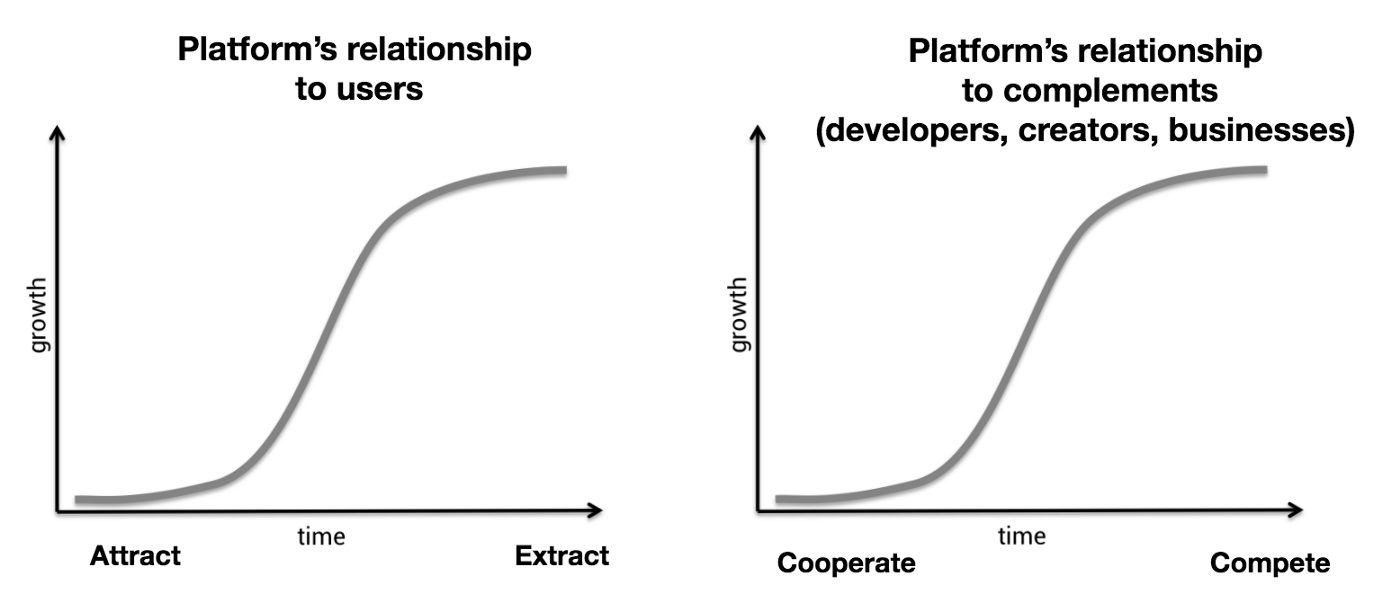

This idea is closely related to censorship resistance and resilience. If you want to build and launch an application or a business on top of a centralized platform like Facebook, you need Facebook’s permission to do so. They may deny you permission, or worse, they may grant it and then suddenly, arbitrarily, unilaterally revoke it later. Just as with censorship, companies do this with impunity, and when it happens to you, you have little to no recourse. Capitalism dictates that when a for-profit, centralized operator controls an active network, they are compelled to eventually begin extracting rents from the network.

The predictable lifecycle of centralized platforms. As they progress along the S-curve, they gain power over both users and complements. Eventually, inevitably, the relationship becomes an extractive one. Image courtesy Chris Dixon (source).

By contrast, no one has control over which applications are hosted on a permissionless platform like Ethereum, by design. Permissionless innovation is a fantastically important topic that I cannot possibly do justice here. The long arc of human history bends towards permissionlessness and as monarchs, church, and state have progressively lost their tight grip over the lives and self expression of the individual, innovation, productivity, and overall quality of life have increased massively as a result.

Decentralization reduces platform risk

To continue with the previous example, if you build an application on Facebook (and receive permission to do so), you have no guarantee that the platform won’t change. In particular, you may rely on some essential feature of the platform such as its API that Facebook may unilaterally decide to change or remove. Indeed, this happens all the time. By contrast, you can safely deploy an application on a decentralized, open source platform such as Ethereum, assured in the knowledge it will continue to operate for a long time and that the rules will not suddenly change.4 What’s more, you can choose to become actively involved in the governance of a decentralized platform and make your voice heard (good luck convincing Facebook to change something for you). As with other decentralized systems, open source projects very rarely “shut down” or “die.” They may be forked, or starved of resources, or the number of users or contributors may decline, but the code is always there and you can always continue to develop or operate it yourself. Good luck doing that with a platform that Google decides to shut down.

Decentralized systems are more egalitarian

In a fully decentralized system, everyone who participates does so as a peer. There is no hierarchy and no centralized class of leaders. Everyone has access to precisely the same information, which reduces information asymmetries. If the system is well-designed, everyone is treated the same. This does not guarantee equality of outcome, but it does increase equality of opportunity. As one concrete example, in the world of Finance 1.0—the world of Goldman Sachs and hedge funds—success depends upon convincing someone to hire you, or else starting your own fund, which is incredibly expensive and time-consuming. For this reason it helps a lot if you already know a lot of successful people, went to a good school, speak English well, etc.. By contrast, in Finance 2.0, firms will be replaced by smart contracts and DAOs, which anyone, anywhere can deploy quickly, cheaply, and permissionlessly.5 Transaction costs and barriers to entry will be much lower. To paraphrase a famous New Yorker cartoon, in Finance 2.0, nobody knows you’re a dog. It will be a lot less about where you come from, what you look like, and who you know, which means that it’ll be much more meritocratic. A meritocracy is far more participatory and reduces the likelihood that an entrenched elite will emerge and stifle competition. In an age when the gap between the rich and the poor, the over- and the underprivileged, is growing rapidly, this matters.6

Decentralized systems are more agile

They’re more adaptive and responsive to local needs and emergent situations. Contrast, for example, two opposing systems of government: an empire, on the one hand, which attempts to enforce the same body of laws everywhere, versus a much looser federation or affiliation, which allows a high degree of autonomy and local sovereignty.7 There’s a reason empires have gone out of fashion: local, autonomous government is more likely to result in a happy citizenry since it gives citizens far greater scope for self-expression and self-determination. It’s interesting to note that agility and local adaptiveness are closely related to resilience, as already noted. In a centralized system, when something goes wrong, each node needs to send a message back to HQ to report the problem and await instructions. By contrast, in a decentralized system, each node is sovereign and can respond immediately and in an autonomous fashion when something goes wrong (within the bounds of a shared protocol).

Decentralized systems are more democratic and inclusive

Because they’re more agile and responsive to local needs, they tend to be less conservative and more progressive. As a result, they’re better able to make room for diverse groups of stakeholders. By factoring in the needs, preferences, and ideas of more people, decentralized systems tend to foster local pockets of creativity, something that cannot happen in a highly centralized bureaucracy. (In other words, less suits, more Burning Man.) By the same token, decentralized systems are better able to enfranchise a large, diverse set of stakeholders by broadly distributing ownership and influence.

Decentralized systems are more scalable

In a centralized system, all information has to flow back to the operator, and the operator has to approve all changes. The operator therefore acts as a bottleneck on growth. This is a fundamental tenet of systems theory and is true of every system, whether firm, state, computer system, or biological system.

Decentralized systems reduce liability

When something goes wrong in a centralized system, one can always blame the system’s operator: witness content platforms like Google and Facebook being forced to quickly identify and remove content deemed inappropriate. The same is not true in a decentralized system, where it’s not always obvious whom to blame, or even whether culpability can be assigned to any single actor or any group of actors.8 Centralization of control invites increased regulatory scrutiny: “every bit of control you have is a liability.” As a result, ironically, operators of even highly profitable centralized networks are considering relinquishing this control via a form of “exit to community.”

In Conclusion

It should be clear from this list that decentralized systems offer a host of benefits over their centralized counterparts, and should thus be considered for any novel system or network design. This is especially the case when properties such as permissionlessness, broad participation and degree of local autonomy, and resilience are requirements. Of course, decentralization does not come without a cost: while such systems are more robust and may arrive at objectively “better” results than their centralized counterparts, there is a high price to pay in coordination cost and thus reduced efficiency. I’ll explore the downsides to decentralized systems in a later article.

Have you designed, built, or transacted on a decentralized system? What was your experience like, compared to centralized alternatives? Have I missed any important benefits of decentralized systems? What do you consider the biggest downside of centralized systems? Hit the Comment button below and let me know!

-

To be more precise, decentralization allows us to be more targeted about where we place trust: in particular, it enables us to place trust in things like systems, and incentives, and math, rather than in people who are fallible. In this respect it’s a lot like, say, contract law, where we don’t necessarily need to trust the person on the other side of the contract, since we know we can fall back on the legal system if something goes wrong. For much more on this topic, see Money, blockchains, and social scalability. ↩

-

In theory. It never works quite this way in practice because no network operates totally in isolation from the rest of the world. In other words, no network can be hermetically sealed off from existing social, economic, and political realities. Off-chain wealth and influence still count for a great deal, even in supposedly neutral, decentralized networks like Bitcoin and Ethereum. It’s important to recognize that, in reality, people are not on equal footing: those who come into the network with greater wealth, influence, or expertise are highly likely to see at least some of that privilege carry over onto the on-chain world. This can impact something as fundamental as what the chain regards as the truth: as concrete examples, witness the Ethereum DAO hard fork, and Binance’s considering a Bitcoin reorg after a theft last year. The Ethereum Foundation and Binance are in fact supernodes in their respective networks because they enjoy a high degree of social and economic influence. In this way, blockchain is a leaky abstraction: permissionless and egalitarian more in theory than in practice. ↩

-

Note that there is an important distinction between censorship and filtering: censorship is bad, but filters are good. Yes, censorship-resistant networks might fill up with spam and distasteful content. No, it’s not a problem, because communities can have codes of conduct and share filters one layer up the stack. It is not censorship if content that violates a particular community’s code of conduct is removed from that community’s forum, as long as the party behind that speech is still free to go elsewhere. ↩

-

Well, they’re less likely to change in big ways that break things. All platforms evolve over time. While governance of decentralized systems tends towards conservativism due to high coordination costs, occasionally big things do happen: witness Ethereum’s DAO hard fork. When they do, you at least have freedom to exit: i.e., to fork the codebase, deviate from the minority, and do your own thing—something else you cannot do with Facebook. ↩

-

Finance 2.0 is emerging in the form of the rapidly evolving #DeFi ecosystem. For the moment, the leaders and beneficiaries of most #DeFi projects in fact look and sound the same as the beneficiaries of Finance 1.0, but I expect and hope that will change over time. ↩

-

This sort of fairness, egalitarianism, credible neutrality, etc., are ideals to aim for, but most projects today that aim for them fall far short. IMHO this is down to governance: you can design a system to be as “decentralized” and “participatory” and “neutral” as you like, but in practice, when effective power is held by a small group of friends who look and sound alike, tend to hang out together at events, etc., the system will tend to favor that group of people at the expense of everyone else. This is one consequence of the Tyranny of Structurelessness and “decentralized”, informal governance. ↩

-

Interestingly, this same continuum holds in the blockchain space, and probably in all distributed systems. Compare the approaches to scaling taken by Ethereum 2 and NEAR (many identical shards) to those of Polkadot (many app chains that all share security) or Cosmos (totally sovereign app chains). ↩

-

This is a fascinating and highly contentious topic in certain decentralized, autonomous systems such as blockchains and smart contracts. I explore this topic at length in Autonocrats & Anthropocrats. ↩